My partner visa has been refused: what are my options

In this post we consider what options you have in the event that your partner visa application is refused. This is a sub post of our guide on How to apply for a UK partner visa.

This post is a collection of thoughts and advice provided over the years to clients who have received a refusal of their partner visa application.

Before we get into it: if you have received a refusal, I am sorry. It is extremely stressful to be in this position.

In summary, you have two main options, which is to either apply again, or to appeal. The aim of this post is to give you a better idea as to which one is best for you, intended to provide general background on the relevant issues.

Whilst we have done our best to ensure that the information here is accurate at the time of writing, the UK immigration rules change frequently, so you should always check the position at the time you make your application or appeal.

This post was written by Nick Nason, director of Edgewater Legal. Book in a free initial call with Nick if you want to discuss getting help with your appeal, or would like to explore what getting help looks like.

What is an appeal?

Where the Home Office refuses a partner visa application, there should be a right of appeal against this decision to the tribunal (which is like a court, but less formal).

You – or your lawyer, if you have one – are required to explain in writing during the appeal process why the Home Office is wrong, and then you can call witnesses and make further arguments at a hearing in front of a judge.

There is usually a Home Office lawyer at the hearing to put their side of the case, and who can ask you and any witnesses questions.

The judge reads the documents and listens to your arguments and makes their decision based on this evidence in a written document called a 'determination'.

If the judge agrees with you, and the Home Office does not appeal to the Upper Tribunal, the original Home Office decision will usually be reversed.

If the judge doesn’t agree, you have the right of appeal. But if you don't succeed in any onward appeal, then the Home Office decision will stand.

How do I know if I have a right of appeal?

If you have made a partner visa application, you should have a right of appeal to the tribunal.

The most straightforward way of discovering whether there is a right of appeal against a Home Office refusal is by reading the decision letter/email or notice of decision provided by the Home Office.

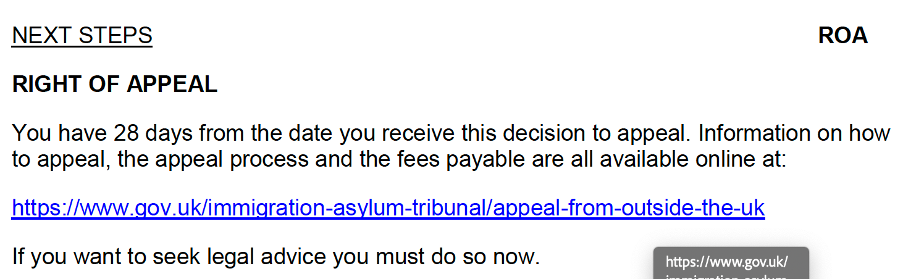

For example, in a decision to refuse entry clearance as a partner (an application from outside of the UK), the wording might look something like this:

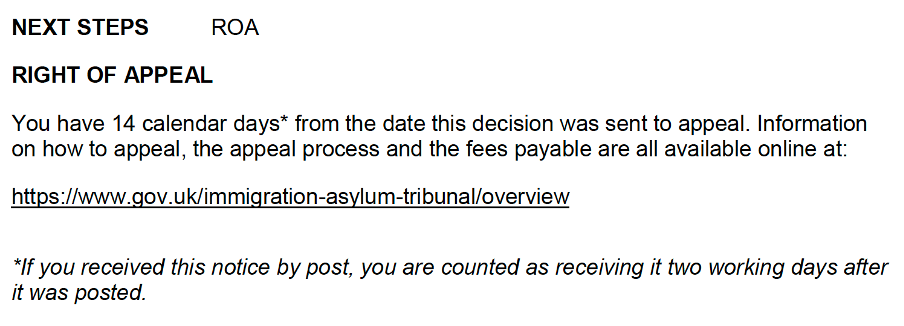

In a decision to refuse a partner application from within the UK, the wording in the decision letter might look something like this:

If your partner visa application has been refused and you have not been given a right of appeal, you should seek legal advice as soon as possible.

Generally, if you are in the UK, you will have 14 days to appeal from the date the decision was sent. If you are outside of the UK, you have 28 days to appeal after you get your decision.

It is important to submit any appeal within the permitted time.

Why has my application been refused?

Once you have established that you have a right of appeal, the next step is to establish why the application has been refused.

Applications can be refused for a range of reasons. The basis of the refusal is an important consideration in deciding whether an appeal or a new application would be the best option.

If an application is refused, for example, because documents or information (which were available or can be straightforwardly obtained) were not provided, then it may be worth considering making a new application, and providing the missing documents or information.

However, if the application was refused because a Home Office caseworker took a different view as to whether the facts and evidence in your case amounted, for example, to 'exceptional circumstances' then it may be worth considering an appeal.

This is because making a new application with the same facts and evidence is unlikely to generate a different result.

But before deciding one way or the other, it is very important to understand …

How long is the tribunal appeal process?

The most important thing to note about the immigration tribunal appeal process is that, at the time of writing, unless the Home Office agrees to withdraw its decision following a review (see below), it is not usually quick.

At the moment it would be unusual to get a resolution – by which we mean a written decision from a judge following a full hearing leading to a reversal of the original decision by the Home Office, and the issue of grant of entry/stay – in less than 9 months.

Instead, via a tribunal appeal, I would usually budget 12-18 months from the point of receiving the refusal through to a full resolution (meaning that you receive what you would have got if your application had not been refused: i.e. a grant of entry/stay).

This is obviously a long time to wait if you are separated from a loved one in another country.

It also assumes that there are no onward appeals from the Home Office – they can appeal to the Upper Tribunal against the decision of the First Tier Tribunal against the decision of the judge – and there are no delays within the tribunal appeals process.

For example, sometimes a hearing date might be set, and the Home Office lawyer is unable to attend, leading to an adjournment (delay) of the case. This happened in a recent case, adding 5 months to the timeline.

Or there may be a delay following an 'allowed' appeal (meaning that you won) decision by a judge which the Home Office – due to capacity issues – takes 6 months to implement. This happened in another recent case.

This time budget of 12-18 months also assumes that you’ll win. And which is why you need to have a clear idea of the merits of your case before embarking on an appeal.

Will the Home Office withdraw its decision if I appeal?

Relatively recently, the tribunal system introduced what it called its ‘reform’ system, a significant feature of which is a ‘review’ stage, where the Home Office is supposed to review the decision early in the process.

The idea is that the appellant provides further documents in support of their case – known as an appellant’s ‘bundle’ of evidence – and a written argument explaining why the decision was wrong, and then the Home Office look again at the application taking this further evidence into account.

An interim report which reviewed the progress of this new process found that from January 2020 until July 2021, 28% of appeals were withdrawn at the review stage.

There was variation by region, with the withdrawal rate being highest in London (43%) and lowest in the North East and North West regions (17% respectively).

The review is supposed to happen fairly early on in the process. Here is an example timeline from a recent case:

- 14 February: refusal

- 8 March: appeal lodged

- 8 June: appellant’s evidence provided

- 24 July: Home Office review undertaken and decision reversed

- 15 October: grant of entry clearance

This case actually involved delay by the Home Office providing its evidence after the lodging of the appeal, and which delayed this process by a few months. The resolution here therefore took 8 months.

So you can see that even if you appeal with a view to persuading the Home Office to withdraw its decision at the review stage, there is still scope for delay.

I would say that in the absolute best-case scenario – in the event that the Home Office withdraw the decision following you making an appeal – you are looking at 4-6 months for a resolution.

Will I win my appeal?

Note that the best-case appeal scenario outlined above involving withdrawal of the decision at the review stage assumes, of course, that the Home Office agree that the original application was wrongly decided and decide to reverse it.

As well as being aware of the timeframes involved in an appeal, it is imperative that you have the clearest possible idea of your chances of success before moving ahead with an appeal.

This will obviously depend from case to case. But if I only had a limited legal budget, this is probably the place I would spend it.

Because you’re about to spend 12+ months in a legal process where, if you don’t succeed, you will be in exactly the same position you are in right now.

So if a lawyer had looked at your case at the point of the refusal and assessed your chances of success as extremely low, you might have decided to simply make a further application at that stage rather than waste a year engaging in a process that was never going to succeed.

So when should I appeal?

Bearing in mind all of the above, there are three main scenarios where an appeal probably makes the most sense.

You can't afford a new application

As you know, every time you make a Home Office application you pay the application and other fees.

Currently this is £1846 from outside the UK, and £1048 in the UK, not including hidden fees. Whilst you will get the Immigration Health Surcharge back if refused, the other fees are not refunded.

Lots of people can’t afford to make a new application, so if this is you, then a tribunal appeal may be the only realistic option to reverse a negative decision.

The tribunal fee is £140, but other than this – assuming you don’t hire a lawyer, instruct experts or need to spend other money preparing your appeal, e.g. translating documents etc – the tribunal appeal is the more cost effective option to obtain a remedy.

Home Office unlikely to change their minds

The tribunal appeal is usually the best option where you don’t believe the Home Office would change its decision if you made a further application, even with additional evidence or information.

For example, you may be arguing in your application that you meet an exception to the rules, but the Home Office does not agree. In these circumstances, an appeal is likely to be the only realistic option.

The question of whether the Home Office would change their minds is of course rarely straightforward, and I would repeat my recommendation that if you have any legal budget for advice from a specialist, this is probably the most efficient/effective place to spend it.

This is a case study involving a case where an appeal was made on the basis that it was unlikely that Home Office was going to change its mind.

Time no issue, strong case

Alternatively, a tribunal appeal process may work in your case if the timeframes outlined above are not a problem.

The length of time it takes for the tribunal to make a decision, and then the time it takes to implement that decision (if positive), is really the main drawback of the appeal process.

So if you’re fine with how long it will take, and are confident in the eventual outcome of the case, then you may feel that a tribunal appeal is worth doing.

I would again repeat that I would always suggest seeking at least some level of legal advice on the merits of a case if you are deciding to appeal, even if you think you are in a strong position.

This is a case study of a strong case where the time was less of an issue than in other cases.

When should I make a further application?

The main benefit of making another application is that the process – if not the outcome – is within a much tighter set of tramlines than a tribunal appeal.

You know that there is a good chance that, if successful in an application, you are going to have a resolution (i.e. a document permitting travel to, or providing a right to reside in, the UK) within 2-4 months of making application, or sooner if you pay for priority processing.

Of course, applications can be delayed, but there is a service standard in which the majority of applications are decided, and the majority of applications are decided much more quickly than the appeal timeframes listed above.

The main downside of making a further application is that you are going to have to spend at least the best part of £2,000 GBP on the process (you should have been refunded the Immigration Health Surcharge fees you paid first time around).

This is of course outrageous, but if you can afford it, and there is something in the application which could be easily resolved with a further application, then it is likely that this would be the best solution in most cases.

As above, the question of how a refused application can be rectified in a future application is not always straightforward, so if you’re going to get advice on any part of the process, I would get it on that.

This post is intended to provide general background on the relevant issues and does not constitute legal advice. The law (and fee rates) may have changed since the date this article was published. You should always take legal advice relating to your individual circumstances.